The first thing that hits you about India is the constant honking. Not angry honking — more like a Morse code. A naturally evolved language whose vocabulary is: ‘I’m here, don’t die, thank you, ’ a simple yet highly effective way of communication that uses widely available low-tech equipment (the horn) to solve a complicated traffic flow problem.

If you have ever seen a junction in India, you’d notice the chaotic, yet fluid way cars, motorcycles, and pedestrians effortlessly go past each other without colliding. What is marshalled through complicated systems of traffic lights and road signs in the West is just working in India in the absence of the former.

Simple Solutions to Complex Problems

A popular story claims that NASA spent millions developing a special space pen. At the same time, the Russians simply used a pencil (in reality, both NASA and the Soviet space program initially used pencils, where only later an independent inventor, Paul Fisher, created the Fisher Space Pen with his own funds). Although a myth, it exemplifies the kind of innovative thinking employed when resources are scarce.

If you visit an Indian railway station, you’ll see that where Western stations have standard fire extinguishers, there are usually three buckets of sand and two buckets of water. While this may seem backwards to the Western eye, it’s actually quite brilliant.

Fire extinguishers have an expiration date, where they need to be serviced or replaced to remain effective. With India’s vast number of railway stations and the huge geographical dispersity, it’s simply unmanageable to keep those in check, where sand and water, which would almost always do the job, are in abundance everywhere. There is no real need for complex compound bottles shipped and constantly maintained where a simple and effective solution would suffice.

The Indian zero-electricity clay refrigerator is yet another example of simple ingenuity. As rural areas have no electricity, but do need to keep vegetables, milk and eggs fresh for a couple of days, an Indian potter designed a clay fridge that can do the job. It costs a fraction of a modern electrical fridge and can be built and transported easily without requiring a full-blown manufacturing facility that relies on multiple components.

The Hero

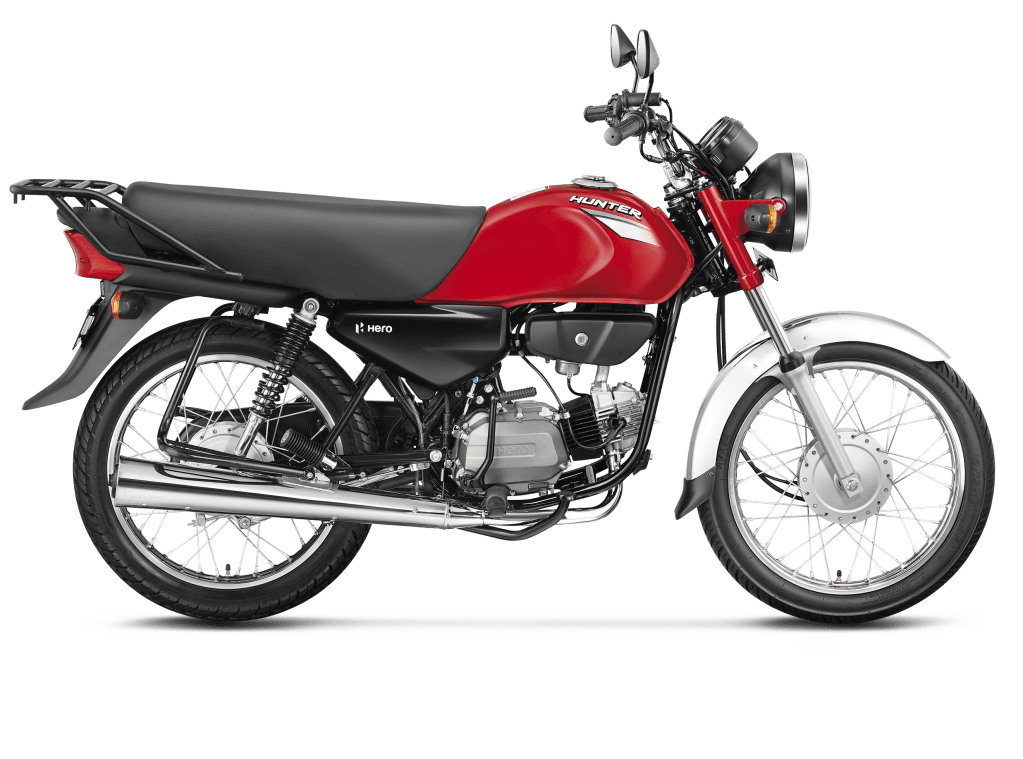

When I first laid eyes on India’s Hero motorcycle, I was amazed at the innovative simplicity of the bike.

To (my) Western eyes, it looked almost primitive with its drum brakes and single piston engine. It took me a while to fully grasp the philosophy behind the seemingly backward design.

Drum brakes, as opposed to disc brakes, are not exposed to mud and harsh weather; they are a closed system that needs no cleaning and does not get bogged down on murky roads where discs would lose braking power.

The single piston, horizontally placed (which is an engine configuration nowhere to be found in Western or Japanese bikes), allows for power to be delivered to the rear wheel with minimal complexity as opposed to V-twin, or DOHC engines, which need complex transmission and timing.

On top of that, Heros are equipped with small engines, ones that are never taken to their limit. After all, no one needs a high-revving sport bike to get themselves from point A to point B in rural India; they need it to not break down.

In layman’s terms, these Heros would run forever with minimal to no maintenance, and if they ever break down, almost anyone with basic tooling can fix them.

It’s a design deeply rooted in a philosophy of simplicity.

Want Not

In Buddhism, contentment with little (Santutthi) refers not to poverty or harsh asceticism, but to an inner freedom from excess desire. It means living simply, being satisfied with what one has, and reducing dependence on possessions, comfort, and constant stimulation. Because craving is seen as the root of suffering, minimising unnecessary wants creates mental clarity, peace, and spaciousness.

Santutthi (or santuṭṭhi) is a Pali term in Buddhism meaning satisfaction, contentment, or joy, representing the ability to be at ease with what one has, even just basic necessities, which fosters inner peace and helps overcome greed, a core teaching in discourses like the Santutthi Sutta. It’s a vital practice for mental well-being, encouraging acceptance of the present moment in meditation and daily life.

Early Buddhism (Theravāda) emphasises meeting only four basic needs—food, clothing, shelter, and medicine—and viewing anything beyond that as potential fuel for craving. Zen and Mahāyāna traditions share the same idea but express it through aesthetic simplicity, presence, and freeing energy to serve others.

Contentment with little is part of the Buddha’s “Middle Way”: not indulgence and not extreme self-denial, but a balanced lifestyle that supports calmness, insight, and liberation. In daily life, it appears as mindful consumption, reducing clutter, simplifying routines, and cultivating appreciation rather than craving.

It is that philosophy that materialises in the innovative-backwards designs such as the ones mentioned earlier. It’s not third-world engineering or lack of resources that drives those designs; it is the cultural focus on removing the noise from daily life and focusing on what really matters, rather than getting webbed-down in endless unnecessary complexity, which serves no one but the ones who (usually commercially) benefit from it.

(Don’t) Go West

This clip from the movie 1923 beautifully portrays the absurdity of Western capitalism, where everything is complex, seemingly advanced, but fundamentally flawed.

As the man in the above 1923 movie clip tells the salesman who tries to convince them to rent an electrical washing machine and fridge, and only pay for the electricity: “We buy all this stuff, we’re not working for ourselves, we’re working for you”. Which kind of nails it.

Western philosophy (mainly Capitalism) encourages and depends on endless economic growth to sustain the system, and consumption as a major driver of the economy. In layman’s terms, you must get all this new stuff or the system breaks. Once you accept those principles, it is obvious that quick salesmen would sell you on complicated solutions to problems you didn’t know you ever had. Those, in turn, would force you to work even harder to buy and maintain the endless stream of complicated things you so proudly own, where in fact all you needed was … less.

It’s a vicious cycle we all (used to) take for granted. After all, who wants to be considered backwards? Third-world, a simpleton.

“Our job is to figure out what they [customers] are going to want before they do. … People don’t know what they want until you show it to them.

Steve Jobs, Apple

To Less and Beyond

As someone who was once deeply entrenched in the Western way of thinking, wanting more, owning more, loving the latest gadgets, and working hard to acquire them, India was, and still is, an eye-opening experience. A culture based on a philosophy of less. Simplified, yet practical designs, longevity instead of infinite (false) growth, human experience rather than object ownership.

It seems to me that Buddha may be a better innovator than Jobs or the Elon Musks of the world, in the same way a Buddhistically-designed motorcycle is better than a sports bike on an Indian road. Because we really want to enjoy the road, not get there as fast as we can.